Value Types vs Reference Types

tl;dr structs have better data locality. Value types add much less pressure for the GC than reference types. But big value types are expensive to copy and you can accidentally box them which is bad.

Introduction

The .NET framework implements Reference Types and Value Types. C# allows us to define custom value types by using struct and enum keywords. class, delegate and interface are for reference types. Primitive types, like byte, char, short, int and long are value types, but developers can’t define custom primitive types. In Java primitive types are also value types, but Java does not expose a possibility to define custom value types for developers ;)

Value Types and Reference Types are very different in terms of performance characteristics. In my next blog posts, I am going to describe ref returns and locals, ValueTask<T> and Span<T>. But I need to clarify this matter first, so the readers can understand the benefits.

Note: To keep my comparison simple I am going to use ValueTuple<int, int> and Tuple<int, int> as the examples.

Memory Layout

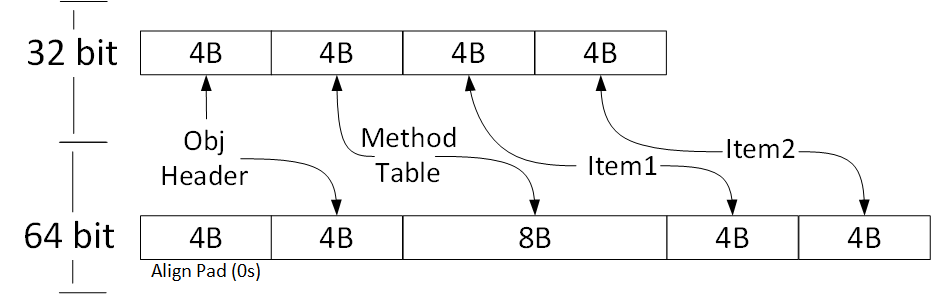

Every instance of a reference type has extra two fields that are used internally by CLR.

ObjectHeaderis a bitmask, which is used by CLR to store some additional information. For example: if you take a lock on a given object instance, this information is stored inObjectHeader.MethodTableis a pointer to the Method Table, which is a set of metadata about given type. If you call a virtual method, then CLR jumps to the Method Table and obtains the address of the actual implementation and performs the actual call.

Both hidden fields size is equal to the size of a pointer. So for 32 bit architecture, we have 8 bytes overhead and for 64 bit 16 bytes.

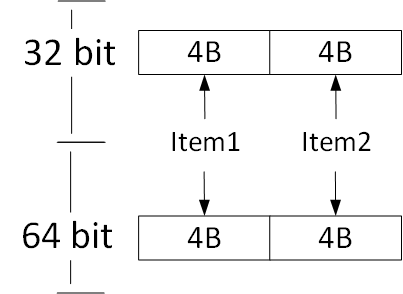

Value Types don’t have any additional overhead members. What you see is what you get. This is why they are more limited in terms of features. You cannot derive from struct, lock it or write finalizer for it.

RAM is very cheap. So, what’s all the fuss about?

CPU Cache

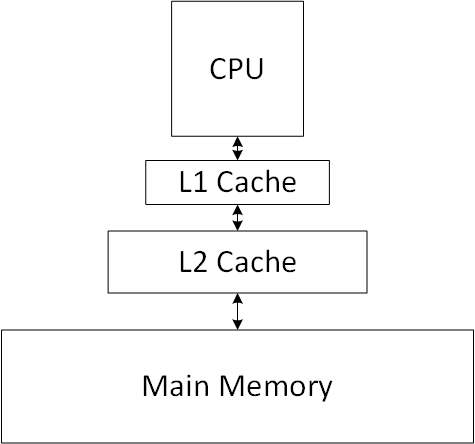

CPU implements numerous performance optimizations. One of them is cache, which is just a memory with the most recently used data.

Note: Multithreading affects CPU cache performance. In order to make it easier to understand, the following description assumes single core.

Whenever you try to read a value, CPU checks the first level of cache (L1). If it’s a hit, the value is being returned. Otherwise, it checks the second level of cache (L2). If the value is there, it’s being copied to L1 and returned. Otherwise, it checks L3 (if it’s present).

If the data is not in the cache, CPU goes to the main memory and copies it to the cache. This is called cache miss.

Latency Numbers Every Programmer Should Know

According to Latency Numbers Every Programmer Should Know going to main memory is really expensive when compared to referencing cache.

| Operation | Time |

|---|---|

| L1 cache reference | 1ns |

| L2 cache reference | 4ns |

| Main memory reference | 100 ns |

So how can we reduce the ratio of cache misses?

Data Locality

CPU is smart, it’s aware of the following data locality principles:

- Spatial

If a particular storage location is referenced at a particular time, then it is likely that nearby memory locations will be referenced in the near future.

- Temporal

If at one point a particular memory location is referenced, then it is likely that the same location will be referenced again in the near future.

CPU is taking advantage of this knowledge. Whenever CPU copies a value from main memory to cache, it is copying whole cache line, not just the value. A cache line is usually 64 bytes. So it is well prepared in case you ask for the nearby memory location.

The .NET Story

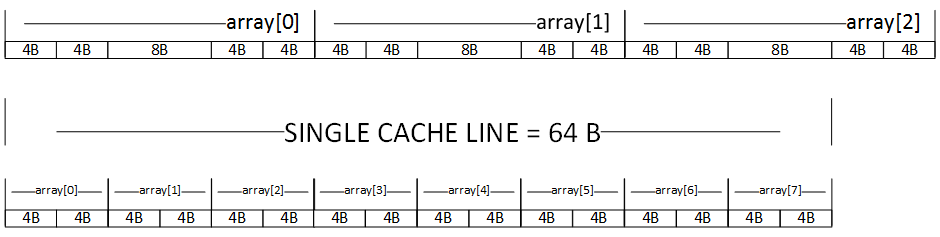

How the two extra fields per every reference type instance affect data locality? Let’s take a look at the following diagram which shows how many instances of ValueTuple<int, int> and Tuple<int, int> can fit into single cache line for 64bit architecture.

For this simple example, the difference is really huge. In our case, we could fit 8 instances of value type and 2.66 reference type.

Benchmarks!

It’s important to know the theory, but we need to run some benchmarks to measure the performance difference. Once again I am using BenchmarkDotNet and its feature called HardwareCounters which allows me to track CPU Cache Misses. Here you can find my blog post about Collecting Hardware Performance Counters with BenchmarkDotNet.

The benchmark is a simple loop with read access in it’s every iteration. I would say that it’s just a CPU cache benchmark.

Note: This benchmark is not a real life scenario. In real life, your struct would most probably be bigger (usually two fields is not enough). Hence the extra overhead of two fields for reference types would have a smaller performance impact. Smaller but still significant in high-performance scenarios!

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args) => BenchmarkRunner.Run<DataLocality>();

}

[HardwareCounters(HardwareCounter.CacheMisses)]

[RyuJitX64Job, LegacyJitX86Job]

public class DataLocality

{

[Params(

100,

1000000,

10000000,

100000000)]

public int Count { get; set; } // for smaller arrays we don't get enough of Cache Miss events

Tuple<int, int>[] arrayOfRef;

ValueTuple<int, int>[] arrayOfVal;

[GlobalSetup]

public void Setup()

{

arrayOfRef = Enumerable.Repeat(1, Count).Select((val, index) => Tuple.Create(val, index)).ToArray();

arrayOfVal = Enumerable.Repeat(1, Count).Select((val, index) => new ValueTuple<int, int>(val, index)).ToArray();

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int IterateValueTypes()

{

int item1Sum = 0, item2Sum = 0;

var array = arrayOfVal;

for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++)

{

ref ValueTuple<int, int> reference = ref array[i];

item1Sum += reference.Item1;

item2Sum += reference.Item2;

}

return item1Sum + item2Sum;

}

[Benchmark]

public int IterateReferenceTypes()

{

int item1Sum = 0, item2Sum = 0;

var array = arrayOfRef;

for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++)

{

ref Tuple<int, int> reference = ref array[i];

item1Sum += reference.Item1;

item2Sum += reference.Item2;

}

return item1Sum + item2Sum;

}

}

The Results

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.8, OS=Windows 8.1 (6.3.9600)

Processor=Intel Core i7-4700MQ CPU 2.40GHz (Haswell), ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2338337 Hz, Resolution=427.6544 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

LegacyJitX86 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

RyuJitX64 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 64bit RyuJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Runtime=Clr

| Method | Jit | Platform | Count | Mean | Scaled | CacheMisses/Op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IterateValueTypes | LegacyJit | X86 | 100 | 68.96 ns | 1.00 | 0 |

| IterateReferenceTypes | LegacyJit | X86 | 100 | 317.49 ns | 4.60 | 0 |

| IterateValueTypes | RyuJit | X64 | 100 | 76.56 ns | 1.00 | 0 |

| IterateReferenceTypes | RyuJit | X64 | 100 | 252.23 ns | 3.29 | 0 |

As you can see the difference (Scaled column) is really significant!

But the CacheMisses/Op column is empty?!? What does it mean? In this case, it means that I run too few loop iterations (just 100).

An explanation for the curious: BenchmarkDotNet is using ETW to collect hardware counters. ETW is simply exposing what the hardware has to offer. Each Performance Monitoring Units (PMU) register is configured to count a specific event and given a sample-after value (SAV). For my PC the minimum Cache Miss HC sampling interval is 4000. In value type benchmark I should get Cache Miss once every 8 loop iterations (cacheLineSize / sizeOf(ValueTuple<int, int>) = 64 / 8 = 8). I have 100 iterations here, so it should be 12 Cache Misses for Benchmark. But the PMU will notify ETW, which will notify BenchmarkDotNet every 4 000 events. So once every 333 (4 000 / 12) benchmark invocation. BenchmarkDotNet implements a heuristic which decides how many times the benchmarked method should be invoked. It this example the method was executed too few times to capture enough of events. So if you want to capture some hardware counters with BenchmarkDotNet you need to perform plenty of iterations! For more info about PMU you can refer to this article by Jackson Marusarz (Intel).

| Method | Jit | Platform | Count | Mean | Scaled | CacheMisses/Op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IterateValueTypes | RyuJit | X64 | 100 000 000 | 88,735,182.11 ns | 1.00 | 3545088 |

| IterateReferenceTypes | RyuJit | X64 | 100 000 000 | 280,721,189.70 ns | 3.16 | 8456940 |

The more loop iterations (Count column), the more Cache Misses events we get. For the iteration of reference types cache misses were 2.38 times more common (8456940 / 3545088).

Note: Accuracy of Hardware Counters diagnoser in BenchmarkDotNet is limited by sampling frequency and additional code performed in the benchmarked process by our Engine. It’s good but not perfect. For more accurate results you should use some profilers like Intel VTune Amplifier.

GC Impact

Reference Types are always allocated on the managed heap (it may change in the future). Heap is managed by Garbage Collector (GC). The allocation of heap memory is fast. The problem is that the deallocation is performed by non-deterministic GC. GC implements own heuristic which allows it to decide when to perform the cleanup. The cleanup itself takes some time. It means that you can not predict when the cleanup will take place and it adds extra overhead.

Value Types can be allocated both on the stack and the heap. Stack is not managed by GC. Anytime you declare a local value type variable it’s allocated on the stack. When method ends, the stack is being unwinded and the value is gone. This deallocation is super fast. And in overall we have less pressure for the GC! The pressure is not equal to zero because anyway, GC traverses stacks, so the deeper the stack the more work it might have.

But the Value Types can be also allocated on the managed heap. If you allocate an array of bytes, then the array is allocated on the managed heap. This content is transparent to GC. They are not reference type instances, so GC does not track them in any way. But when the small array of value types gets promoted to older GC generation, the content will be copied by the GC.

Benchmarks

Let’s run some benchmark that includes the cost of allocation and deallocation for Value Types and Reference Types.

[Config(typeof(AllocationsConfig))]

public class NoGC

{

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public ValueTuple<int, int> CreateValueTuple() => ValueTuple.Create(0, 0);

[Benchmark]

public Tuple<int, int> CreateTuple() => Tuple.Create(0, 0);

}

public class AllocationsConfig : ManualConfig

{

public AllocationsConfig()

{

var gcSettings = new GcMode

{

Force = false // tell BenchmarkDotNet not to force GC collections after every iteration

};

const int invocationCount = 1 << 20; // let's run it very fast, we are here only for the GC stats

Add(Job

.RyuJitX64 // 64 bit

.WithInvocationCount(invocationCount)

.With(gcSettings.UnfreezeCopy()));

Add(Job

.LegacyJitX86 // 32 bit

.WithInvocationCount(invocationCount)

.With(gcSettings.UnfreezeCopy()));

Add(MemoryDiagnoser.Default);

}

}

The Results

If you are not familiar with the output produced by BenchmarkDotNet with Memory Diagnoser enabled, you can read my dedicated blog post to find out how to read these results.

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.8, OS=Windows 8.1 (6.3.9600)

Processor=Intel Core i7-4700MQ CPU 2.40GHz (Haswell), ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2338337 Hz, Resolution=427.6544 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Job-QZDRYZ : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Job-XFJRTH : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 64bit RyuJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Runtime=Clr Force=False InvocationCount=1048576

| Method | Jit | Platform | Gen 0 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CreateValueTuple | LegacyJit | X86 | - | 0 B |

| CreateTuple | LegacyJit | X86 | 0.0050 | 16 B |

| CreateValueTuple | RyuJit | X64 | - | 0 B |

| CreateTuple | RyuJit | X64 | 0.0076 | 24 B |

As you can see, creating Value Types means No GC (- in Gen 0 column).

Note: If value type contains reference types GC will emit write barriers for write access to the reference fields. So No GC is not 100% true for value types that contain references.

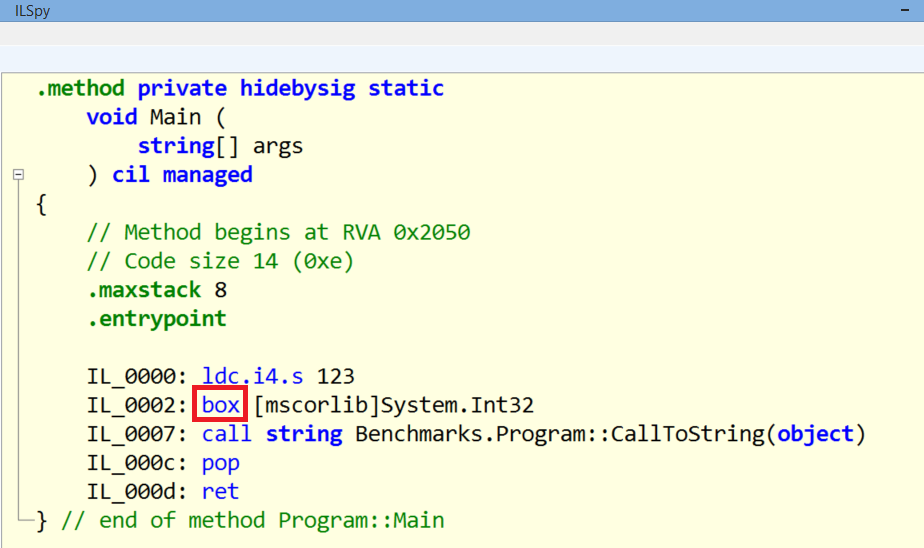

Boxing

Whenever a reference is required value types are being boxed. When the CLR boxes a value type, it wraps the value inside a System.Object and stores it on the managed heap. GC tracks references to boxed Value Types! This is something you definitely want to avoid.

Obvious boxing example:

string CallToString(object input) => input.ToString();

int value = 123;

var text = CallToString(value);

CallToString accepts object. CLR needs to box the value before passing it to this method. It’s clear when you analyse the IL code:

Note: You can use ReSharper’s Heap Allocation Viewer plugin to detect boxing in your code.

Invoking interface methods with Value Types

The previous example was obvious. But what happens when we try to pass a struct to a method that accepts interface instance? Let’s take a look.

[MemoryDiagnoser]

[RyuJitX64Job, LegacyJitX86Job]

public class ValueTypeInvokingInterfaceMethod

{

interface IInterface

{

void DoNothing();

}

class ReferenceTypeImplementingInterface : IInterface

{

public void DoNothing() { }

}

struct ValueTypeImplementingInterface : IInterface

{

public void DoNothing() { }

}

private ReferenceTypeImplementingInterface reference = new ReferenceTypeImplementingInterface();

private ValueTypeImplementingInterface value = new ValueTypeImplementingInterface();

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public void ValueType() => AcceptingInterface(value);

[Benchmark]

public void ReferenceType() => AcceptingInterface(reference);

void AcceptingInterface(IInterface instance) => instance.DoNothing();

}

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.8, OS=Windows 8.1 (6.3.9600)

Processor=Intel Core i7-4700MQ CPU 2.40GHz (Haswell), ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2338337 Hz, Resolution=427.6544 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

LegacyJitX86 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

RyuJitX64 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 64bit RyuJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Runtime=Clr

| Method | Jit | Platform | Mean | Scaled | Gen 0 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ValueType | LegacyJit | X86 | 5.738 ns | 1.00 | 0.0038 | 12 B |

| ReferenceType | LegacyJit | X86 | 1.910 ns | 0.33 | - | 0 B |

| ValueType | RyuJit | X64 | 5.754 ns | 1.00 | 0.0076 | 24 B |

| ReferenceType | RyuJit | X64 | 1.845 ns | 0.32 | - | 0 B |

Once again we got into boxing. Did you expect it?!

How to avoid boxing with value types that implement interfaces?

We need to use generic constraints. The method should not accept IInterface but T which implements IInterface.

void Trick<T>(T instance)

where T : IInterface

{

instance.Method();

}

Benchmarks

[MemoryDiagnoser]

[RyuJitX64Job]

public class ValueTypeInvokingInterfaceMethodSmart

{

// IInterface, ReferenceTypeImplementingInterface, ValueTypeImplementingInterface and fields are declared in previous benchmark

[Benchmark(Baseline = true, OperationsPerInvoke = 16)]

public void ValueType()

{

AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value);

AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value);

AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value);

AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value); AcceptingInterface(value);

}

[Benchmark(OperationsPerInvoke = 16)]

public void ValueTypeSmart()

{

AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value);

AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value);

AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value);

AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value);

AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value); AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface(value);

}

[Benchmark(OperationsPerInvoke = 16)]

public void ReferenceType()

{

AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference);

AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference);

AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference);

AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference); AcceptingInterface(reference);

}

void AcceptingInterface(IInterface instance) => instance.DoNothing();

void AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface<T>(T instance)

where T : IInterface

{

instance.DoNothing();

}

}

Note: I have used OperationsPerInvoke feature of BenchmarkDotNet which is very usefull for nano-benchmarks.

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.8, OS=Windows 8.1 (6.3.9600)

Processor=Intel Core i7-4700MQ CPU 2.40GHz (Haswell), ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2338337 Hz, Resolution=427.6544 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

RyuJitX64 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 64bit RyuJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Job=RyuJitX64 Jit=RyuJit Platform=X64

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Scaled | Gen 0 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ValueType | 5.572 ns | 0.0322 ns | 0.0252 ns | 1.00 | 0.0076 | 24 B |

| ValueTypeSmart | 1.145 ns | 0.0101 ns | 0.0094 ns | 0.21 | - | 0 B |

| ReferenceType | 2.212 ns | 0.0096 ns | 0.0081 ns | 0.40 | - | 0 B |

By applying this simple trick we were able to not only avoid boxing but also outperform reference type interface method invocation! It was possible due to the optimization performed by JIT. I am going to call it method de-virtualization because I don’t have a better name for it. How does it work? Let’s consider following example:

Note: Previous version of this blog post had a bug, which was spotted by Fons Sonnemans. There is no need for extra struct constraint to avoid boxing. Thank you Fons!

public void Method<T>(T instance)

where T : IDisposable

{

instance.Dispose();

}

When the T is constrained with where T : INameOfTheInterface, the C# compiler emits additional IL instruction called constrained (Docs).

.method public hidebysig

instance void Method<([mscorlib]System.IDisposable) T> (

!!T 'instance'

) cil managed

{

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ldarga.s 'instance'

IL_0002: constrained. !!T

IL_0008: callvirt instance void [mscorlib]System.IDisposable::Dispose()

IL_000d: ret

} // end of method C::Method

If the method is not generic, there is no constraint and the instance can be anything: value or reference type. In case it’s value type, the JIT performs boxing. When the method is generic, JIT compiles a separate version of it per every value type. Which prevents boxing! How does it work?

JIT handles value types in a different way than reference types. Operations, like passing to a method or returning from it are the same for all reference types. We always deal with pointers, which have single, same size for all reference types. So JIT is reusing the compiled generic code for reference types because it can treat them in the same way. Imagine an array of objects or strings. From JITs perspective, it is just an array of pointers. So the array’s indexer implementation will be the same for all reference types.

Value Types are different. Each of them can have different size. For example passing integer and custom struct with two integer fields to a method has a different native implementation. In one case we push single int to the stack, in the other, we might need to move two fields to the registers, and then push them to the stack. So it’s different per every value type.

This is why JIT compiles ever generic method/type separately for generic value types arguments.

Method<object>(); // JIT compiled code is common for all reference types

Method<string>(); // JIT compiled code is common for all reference types

Method<int>(); // dedicated version for int

Method<long>(); // dedicated version for long

Method<DateTime>(); // dedicated version for DateTime

It might lead to generic Code Bloat. But the great thing is that at this point in time, JIT can compile tailored code per type. And since the type is know, it can replace virtual call with direct call. As Victor Baybekov mentioned in the comments, it can even remove the unnecessary null check for the call. It’s value type, so it can not be null. Inlining is also possible.

For small methods, which are executed very often, like .Equals() in custom Dictionary implementation it can be very big performance gain.

We can see the effect of inlining if we run the same benchmarks for .NET 4.7, where RyuJit got improved and inlines all calls to AcceptingSomethingThatImplementsInterface.

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.9.313-nightly, OS=Windows 8.1 (6.3.9600)

Processor=Intel Core i7-4700MQ CPU 2.40GHz (Haswell), ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2338348 Hz, Resolution=427.6523 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : .NET Framework 4.6.1 (CLR 4.0.30319.42000), 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.7.2106.0

LegacyJitX64 : .NET Framework 4.6.1 (CLR 4.0.30319.42000), 64bit LegacyJIT/clrjit-v4.7.2106.0;compatjit-v4.7.2106.0

LegacyJitX86 : .NET Framework 4.6.1 (CLR 4.0.30319.42000), 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.7.2106.0

RyuJitX64 : .NET Framework 4.6.1 (CLR 4.0.30319.42000), 64bit RyuJIT-v4.7.2106.0

| Method | Job | Jit | Platform | Mean | Error | StdDev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ValueTypeSmart | LegacyJitX64 | LegacyJit | X64 | 1.2906 ns | 0.0217 ns | 0.0182 ns |

| ValueTypeSmart | LegacyJitX86 | LegacyJit | X86 | 0.3367 ns | 0.0064 ns | 0.0060 ns |

| ValueTypeSmart | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 0.0004 ns | 0.0006 ns | 0.0005 ns |

Note: If you would like to play with generated IL code you can use the awesome SharpLab.

Copying

In C# by default Value Types are passed to methods by value. It means that the Value Type instance is copied every time we pass it to a method. Or when we return it from a method. The bigger the Value Type is, the more expensive it is to copy it. For small value types, the JIT compiler might optimize the copying (inline the method, use registers for copying & more).

[RyuJitX64Job, LegacyJitX86Job]

public class CopyingValueTypes

{

class ReferenceType1Field { int X; }

class ReferenceType2Fields { int X, Y; }

class ReferenceType3Fields { int X, Y, Z; }

struct ValueType1Field { int X; }

struct ValueType2Fields { int X, Y; }

struct ValueType3Fields { int X, Y, Z; }

ReferenceType1Field fieldReferenceType1Field = new ReferenceType1Field();

ReferenceType2Fields fieldReferenceType2Fields = new ReferenceType2Fields();

ReferenceType3Fields fieldReferenceType3Fields = new ReferenceType3Fields();

ValueType1Field fieldValueType1Field = new ValueType1Field();

ValueType2Fields fieldValueType2Fields = new ValueType2Fields();

ValueType3Fields fieldValueType3Fields = new ValueType3Fields();

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)] ReferenceType1Field Return(ReferenceType1Field instance) => instance;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)] ReferenceType2Fields Return(ReferenceType2Fields instance) => instance;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)] ReferenceType3Fields Return(ReferenceType3Fields instance) => instance;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)] ValueType1Field Return(ValueType1Field instance) => instance;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)] ValueType2Fields Return(ValueType2Fields instance) => instance;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)] ValueType3Fields Return(ValueType3Fields instance) => instance;

[Benchmark(OperationsPerInvoke = 16)]

public void TestReferenceType1Field()

{

var instance = fieldReferenceType1Field;

instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance);

instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance);

instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance);

instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance); instance = Return(instance);

}

// removed

}

The rest of the code was removed for brevity. You can find full code here.

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.8, OS=Windows 8.1 (6.3.9600)

Processor=Intel Core i7-4700MQ CPU 2.40GHz (Haswell), ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2338337 Hz, Resolution=427.6544 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

LegacyJitX86 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1649.1

RyuJitX64 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 64bit RyuJIT-v4.6.1649.1

Runtime=Clr

| Method | Jit | Platform | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| TestReferenceType1Field | LegacyJit | X86 | 1.399 ns |

| TestReferenceType2Fields | LegacyJit | X86 | 1.392 ns |

| TestReferenceType3Fields | LegacyJit | X86 | 1.388 ns |

| TestReferenceType1Field | RyuJit | X64 | 1.737 ns |

| TestReferenceType2Fields | RyuJit | X64 | 1.770 ns |

| TestReferenceType3Fields | RyuJit | X64 | 1.711 ns |

Passing and returning Reference Types is size-independent. Only a copy of the pointer is passed. And pointer can always fit into CPU register. ```

| Method | Jit | Platform | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| TestValueType1Field | LegacyJit | X86 | 1.410 ns |

| TestValueType2Fields | LegacyJit | X86 | 6.859 ns |

| TestValueType3Fields | LegacyJit | X86 | 6.837 ns |

| TestValueType1Field | RyuJit | X64 | 1.465 ns |

| TestValueType2Fields | RyuJit | X64 | 8.403 ns |

| TestValueType3Fields | RyuJit | X64 | 2.627 ns |

The bigger the Value Type is, the more expensive copying is.

Have you noticed that TestValueType3Fields was faster than TestValueType2Fields for RyuJit? To answer the question why we would need to analyse the generated native assembly code.

How can we avoid copying big Value Types? We should pass and return them by Reference! I am going to leave it here, and continue with my ref returns and locals blog post next week.

Summary

- Every instance of a reference type has two extra fields used internally by CLR.

- Value Types have no hidden overhead, so they have better data locality.

- Reference Types are managed by GC. It tracks the references, offers fast allocation and expensive, non-deterministic deallocation.

- Value Types are not managed by the GC. Value Types = No GC. And No GC is better than any GC!

- Whenever a reference is required value types are being boxed. Boxing is expensive, adds an extra pressure for the GC. You should avoid boxing if you can.

- By using generic constraints we can avoid boxing and even de-virtualize interface method calls for Value Types!

- Value Types are passed to and returned from methods by Value. So by default, they are copied all the time.

VERY Important!! Pro .NET Performance book by Sasha Goldshtein, Dima Zurbalev, Ido Flatow has a whole chapter dedicated to Type Internals. If you want to learn more about it, you should definitely read it. It’s the best source available, my blog post is just an overview!

Sources

- Pro .NET Performance book by Sasha Goldshtein, Dima Zurbalev, Ido Flatow

- How does Object.GetType() really work? blog post by Konrad Kokosa

- Safe Systems Programming in C# and .NET video by Joe Duffy

- Memory Systems article by University Of Mary Washington

- Latency Numbers Every Programmer Should Know article by Berkeley University

- Types of locality definition by Wikipedia

- Understanding How General Exploration Works in Intel® VTune™ Amplifier XE by Jackson Marusarz (Intel)

- A new stackalloc operator for reference types with CoreCLR and Roslyn blog post by Alexandre Mutel

- Boxing and Unboxing article by MSDN

- Heap Allocations Viewer plugin blog post by Matt Ellis (JetBrains)

- SharpLab.io

- OpCodes.Constrained Field article by MSDN

- .NET Generics and Code Bloat article by MSDN

- What happens with a generic constraint that removes this requirement? Stack Overflow answer by Eric Lippert