Pooling large arrays with ArrayPool

tl;dr Use ArrayPool<T> for large arrays to avoid Full GC.

Introduction

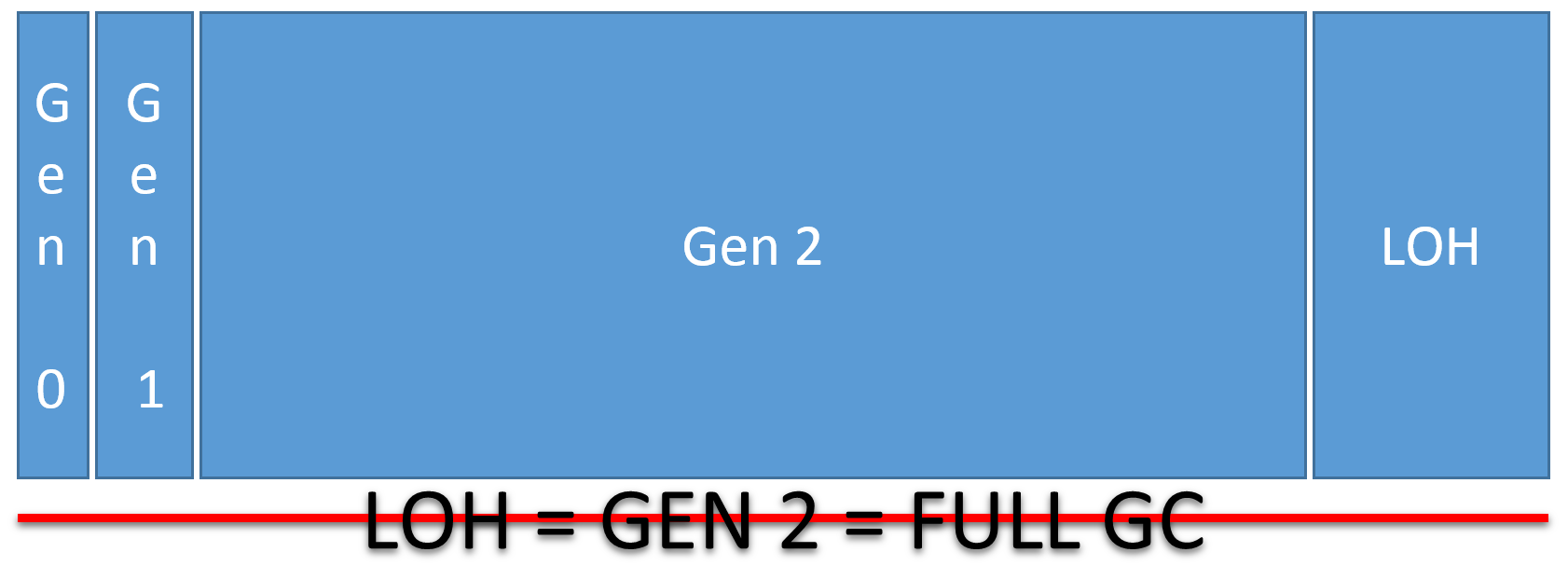

.NET’s Garbage Collector (GC) implements many performance optimizations. One of them, the generational model assumes that young objects die quickly, whereas old live longer. This is why managed heap is divided into three Generations. We call them Gen 0 (youngest), Gen 1 (short living) and Gen 2 (oldest). New objects are allocated in Gen 0. When GC tries to allocate a new object and Gen 0 is full, it performs the Gen 0 cleanup. So it performs a partial cleanup (Gen 0 only)! It is traversing the object’s graph, starting from the roots (local variables, static fields & more) and marks all of the referenced objects as living objects.

This is the first phase, called “mark”. This phase can be nonblocking, everything else that GC does is fully blocking. GC suspends all of the application threads to perform next steps!

Living objects are being promoted (most of the time moved == copied!) to Gen 1, and the memory of Gen 0 is being cleaned up. Gen 0 is usually very small, so this is very fast. In a perfect scenario, which could be a web request, none of the objects survive. All allocated objects should die when the request ends. So GC just sets the next object pointer to the beginning of Gen 0. After some Gen 0 collections, we get to the situation, when Gen 1 is also full, so GC can’t just promote more objects to it. Then it simply collects Gen 1 memory. Gen 1 is also small, so it’s fast. Anyway, the Gen 1 survivors are being promoted to Gen 2. Gen 2 objects are supposed to be long living objects. Gen 2 is very big and it’s very time-consuming to collect its memory. So garbage collection of Gen 2 is something that we want to avoid. Why? let’s take a look at the following video to find out how the Gen 2 collection can affect user experience:

Large Object Heap (LOH)

When GC is promoting objects to next generation it’s copying the memory. As you can imagine, it would be very time-consuming for large objects like big arrays or strings. This is why GC has another optimization. Any object that is bigger than 85 000 bytes is considered to be large. Large objects are stored in a separate part of the managed heap, called Large Object Heap (LOH). This part is managed with free list algorithm. It means that GC has a list of free segments of memory, and when we want to allocate something big, it’s searching through the list to find a feasible segment of memory for it. So large objects are by default never moved in memory.

However, if you run into LOH fragmentation issues you need to compact LOH. Since .NET 4.5.1 you can do this on demand.

The Problem

When a large object is allocated, it’s marked as Gen 2 object. Not Gen 0 as for small objects. The consequences are that if you run out of memory in LOH, GC cleans up whole managed heap, not only LOH. So it cleans up Gen 0, Gen 1 and Gen 2 including LOH. This is called full garbage collection and is the most time-consuming garbage collection. For many applications, it can be acceptable. But definitely not for high-performance web servers, where few big memory buffers are needed to handle an average web request (read from a socket, decompress, decode JSON & more).

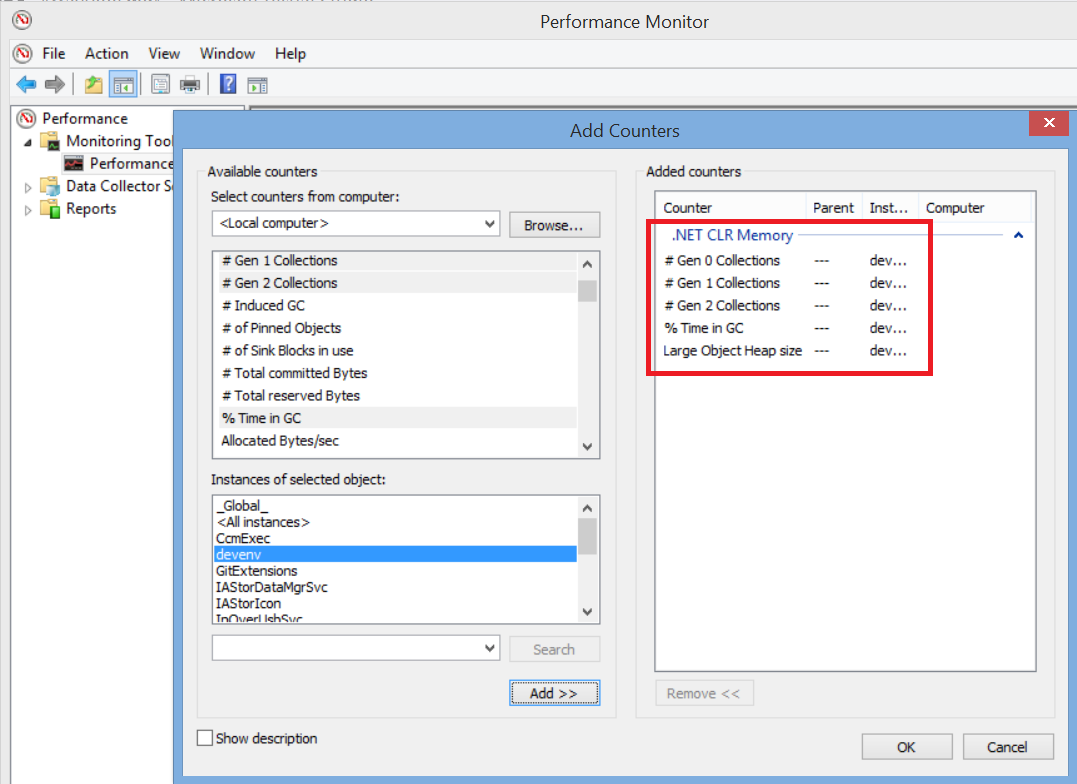

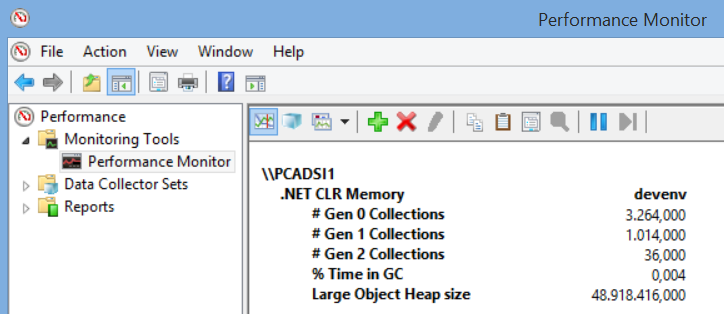

Is it a problem for your application? You can use the built-in perfmon.exe to get an initial overview.

As you can see it’s not a problem for my Visual Studio. It was running for few hours and #Gen 2 Collections is very low compared to Gen 0/1.

The Solution

The solution is very simple: buffer pooling. Pool is a set of initialized objects that are ready to use. Instead of allocating a new object, we rent it from the pool. Once we are done using it, we return it to the pool. Every large managed object is an array or an array wrapper (string contains a length field and an array of chars). So we need to pool arrays to avoid this problem.

ArrayPool<T> is a high performance pool of managed arrays. You can find it in System.Buffers package and it’s source code is available on GitHub. It’s mature and ready to use in the production. It targets .NET Stadard 1.1 which means that you can use it not only in your new and fancy .NET Core apps, but also in the existing .NET 4.5.1 apps as well!

Sample

var samePool = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared;

byte[] buffer = samePool.Rent(minLength);

try

{

Use(buffer);

}

finally

{

samePool.Return(buffer);

// don't use the reference to the buffer after returning it!

}

void Use(byte[] buffer) // it's an array

How to use it?

First of all you need to obtain an instance of the pool. You can do in at least three ways:

- Recommended: use the

ArrayPool<T>.Sharedproperty, which returns a shared pool instance. It’s thread safe and all you need to remember is that it has a default max array length, equal to2^20(1024*1024 = 1 048 576). - Call the static

ArrayPool<T>.Createmethod, which creates a thread safe pool with custommaxArrayLengthandmaxArraysPerBucket. You might need it if the default max array length is not enough for you. Please be warned, that once you create it, you are responsible for keeping it alive. - Derive a custom class from abstract

ArrayPool<T>and handle everything on your own.

Next thing is to call the Rent method which requires you to specify minimum length of the buffer. Keep in mind, that what Rent returns might be bigger than what you have asked for.

byte[] webRequest = request.Bytes;

byte[] buffer = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(webRequest.Length);

Array.Copy(

sourceArray: webRequest,

destinationArray: buffer,

length: webRequest.Length); // webRequest.Length != buffer.Length!!

Once you are done using it, you just Return it to the SAME pool. Return method has an overload, which allows you to cleanup the buffer so subsequent consumer via Rent will not see the previous consumer’s content. By default the contents are left unchanged.

Very imporant note from ArrayPool code:

Once a buffer has been returned to the pool, the caller gives up all ownership of the buffer and must not use it. The reference returned from a given call to Rent must only be returned via Return once.

It means, that the developer is responsible for doing things right. If you keep using the reference to the buffer after returning it to the pool, you are risking unexpected behavior. As far as I know, there is no static code analysis tool that can verify the correct usage (as of today). ArrayPool is part of the corefx library, it’s not a part of the C# language.

The Benchmarks!!!

Let’s use BenchmarkDotNet and compare the cost of allocating arrays with the new operator vs pooling them with ArrayPool<T>. To make sure that allocation benchmark is including time spent in GC, I am configuring BenchmarkDotNet explicity to not force GC collections. Pooling is combined cost of Rent and Return. I am running the benchmarks for .NET Core 2.0, which is important because it has faster version of ArrayPool<T>. For .NET Core 2.0 ArrayPool<T> is part of the clr, whereas older frameworks use corefx version. Both versions are really fast, comparison of them and analysis of their design could be a separate blog post.

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args) => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Pooling>();

}

[MemoryDiagnoser]

[Config(typeof(DontForceGcCollectionsConfig))] // we don't want to interfere with GC, we want to include it's impact

public class Pooling

{

[Params((int)1E+2, // 100 bytes

(int)1E+3, // 1 000 bytes = 1 KB

(int)1E+4, // 10 000 bytes = 10 KB

(int)1E+5, // 100 000 bytes = 100 KB

(int)1E+6, // 1 000 000 bytes = 1 MB

(int)1E+7)] // 10 000 000 bytes = 10 MB

public int SizeInBytes { get; set; }

private ArrayPool<byte> sizeAwarePool;

[GlobalSetup]

public void GlobalSetup()

=> sizeAwarePool = ArrayPool<byte>.Create(SizeInBytes + 1, 10); // let's create the pool that knows the real max size

[Benchmark]

public void Allocate()

=> DeadCodeEliminationHelper.KeepAliveWithoutBoxing(new byte[SizeInBytes]);

[Benchmark]

public void RentAndReturn_Shared()

{

var pool = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared;

byte[] array = pool.Rent(SizeInBytes);

pool.Return(array);

}

[Benchmark]

public void RentAndReturn_Aware()

{

var pool = sizeAwarePool;

byte[] array = pool.Rent(SizeInBytes);

pool.Return(array);

}

}

public class DontForceGcCollectionsConfig : ManualConfig

{

public DontForceGcCollectionsConfig()

{

Add(Job.Default

.With(new GcMode()

{

Force = false // tell BenchmarkDotNet not to force GC collections after every iteration

}));

}

}

The Results

If you are not familiar with the output produced by BenchmarkDotNet with Memory Diagnoser enabled, you can read my dedicated blog post to find out how to read these results.

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.7, OS=Windows 10 Redstone 1 (10.0.14393)

Processor=Intel Core i7-6600U CPU 2.60GHz (Skylake), ProcessorCount=4

Frequency=2742189 Hz, Resolution=364.6722 ns, Timer=TSC

dotnet cli version=2.0.0-preview1-005977

[Host] : .NET Core 4.6.25302.01, 64bit RyuJIT

Job-EBWZVT : .NET Core 4.6.25302.01, 64bit RyuJIT

| Method | SizeInBytes | Mean | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocate | 100 | 8.078 ns | 0.0610 | - | - | 128 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 100 | 44.219 ns | - | - | - | 0 B |

For very small chunks of memory the default allocator can be faster.

| Method | SizeInBytes | Mean | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocate | 1 000 | 41.330 ns | 0.4880 | 0.0000 | - | 1024 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 1 000 | 43.739 ns | - | - | - | 0 B |

For 1 000 bytes they are almost on par.

| Method | SizeInBytes | Mean | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocate | 10 000 | 374.564 ns | 4.7847 | 0.0000 | - | 10024 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 10 000 | 44.223 ns | - | - | - | 0 B |

The bigger it gets, the slower it takes to allocate the memory.

| Method | SizeInBytes | Mean | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocate | 100 000 | 3,637.110 ns | 31.2497 | 31.2497 | 31.2497 | 100024 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 100 000 | 46.649 ns | - | - | - | 0 B |

Gen 2 collections! 100 000 > 85 000, so we get our first Full Garbage Collections!

| Method | SizeInBytes | Mean | StdDev | Gen 0/1/2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 100 | 44.219 ns | 0.0314 ns | - | 0 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 1 000 | 43.739 ns | 0.0337 ns | - | 0 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 10 000 | 44.223 ns | 0.0333 ns | - | 0 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 100 000 | 46.649 ns | 0.0346 ns | - | 0 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 1 000 000 | 42.423 ns | 0.0623 ns | - | 0 B |

At this point of time, you should have noticed, that the cost of pooling with ArrayPool<T> is constant and size-independent! It’s great, because you can predict the behaviour of your code.

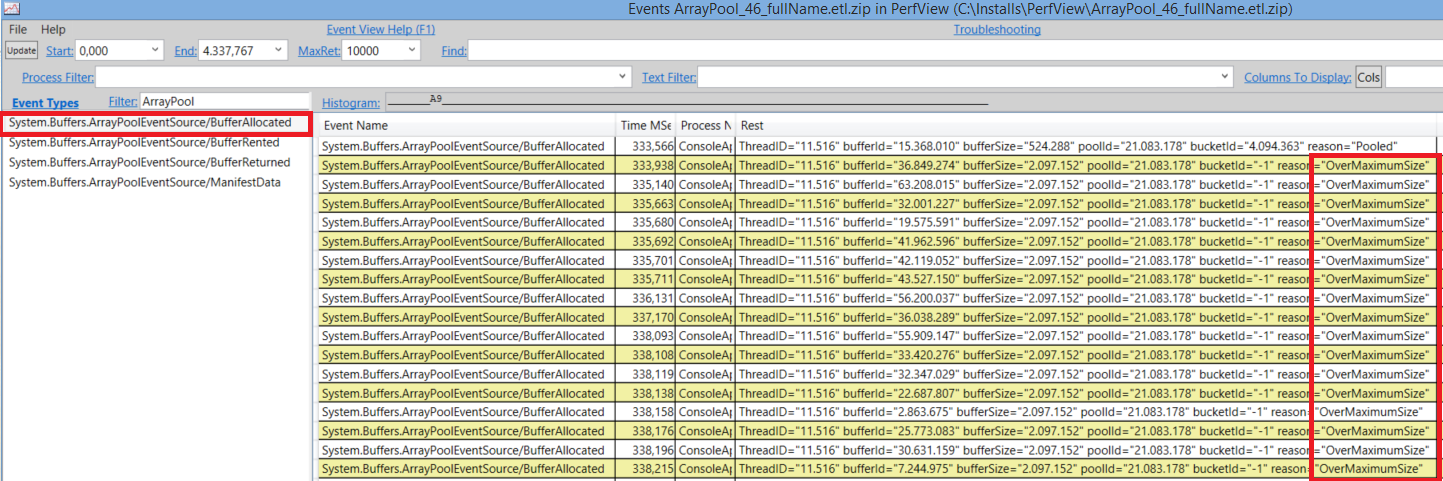

BufferAllocated

But what happens if you try to rent a buffer, that exceeds the max array length of given pool (2^20 for ArrayPool.Shared)?

| Method | SizeInBytes | Mean | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocate | 10 000 000 | 557,963.968 ns | 211.5625 | 211.5625 | 211.5625 | 10000024 B |

| RentAndReturn_Shared | 10 000 000 | 651,147.998 ns | 207.1484 | 207.1484 | 207.1484 | 10000024 B |

| RentAndReturn_Aware | 10 000 000 | 47.033 ns | - | - | - | 0 B |

A new buffer is allocated every time you ask for more than the max array length! And when you return it to the pool, it’s just being ignored. Not somehow added to the pool.

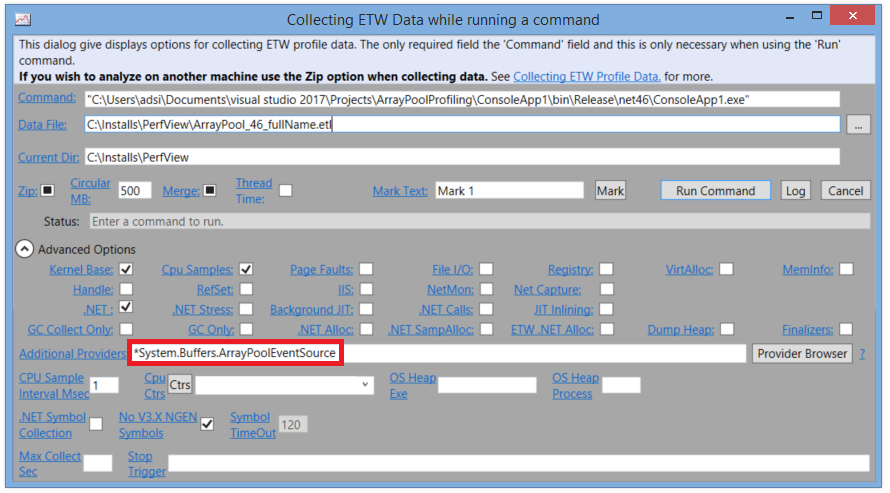

Don’t worry! ArrayPool<T> has it’s own ETW Event Provider, so you can use PerfView or any other tool to profile or monitor your application and watch for the BufferAllocated event.

To avoid this problem you can use ArrayPool<T>.Create method, which creates a pool with custom maxArrayLength. But don’t create too many custom pools!! The goal of pooling is to keep LOH small. If you create too many pools, you will end up with large LOH, full of big arrays that can not be reclaimed by GC (because they are going to be rooted by your custom pools). This is why all popular libraries like ASP.NET Core or ImageSharp use ArrayPool<T>.Shared only.

If you start using ArrayPool<T>.Shared instead of allocating with new operator, then in the pessimistic scenario (asking it for array > default max size) you will be slightly slower than before (you will do an extra check and then allocate). But in the optimistic scenario, you will be much faster, because you will just rent it from the pool. So this is why I believe that you can use ArrayPool<T>.Shared by default. ArrayPool<T>.Create should be used if BufferAllocated events are frequent.

Pooling MemoryStream(s)

Sometimes an array might be not enough to avoid LOH allocations. An example can be 3rd party api that accepts Stream instance. Thanks to Victor Baybekov I have discovered Microsoft.IO.RecyclableMemoryStream. This library provides pooling for MemoryStream objects. It was designed by Bing engineers to help with LOH issues. For more details you can go this blog post by Ben Watson.

Summary

- LOH = Gen 2 = Full GC = bad performance

- ArrayPool was designed for best possible performance

- Pool the memory if you can control the lifetime

- Use

ArrayPool<T>.Sharedby default - Pool allocates the memory for

buffers > maxArrayLength - The fewer pools, the smaller LOH, the better!

Sources

- Server GC video by Age of Ascent

- Source code: CoreFx and CoreClr repos

- Pro .NET Performance book by Sasha Goldshtein, Dima Zurbalev, Ido Flatow

- Fundamentals of Garbage Collection article by MSDN

- Large Object Heap Uncovered article by Maoni Stephens

- No More Memory Fragmentation on the .NET Large Object Heap article by Mario Hewardt

- Announcing Microsoft.IO.RecycableMemoryStream article by Ben Watson